Dark Green Of Neither Earth Nor Sky (photographic installation with video, 2020, in collaboration with Karlis Bergs)

Exhibited:

The MAK Center Los Angeles, CA 2020

About 5,000 private surveillance cameras around the United States are available online because the owners connected them to the internet, but never changed the login and password. These cameras were set up to guard various spaces that are or were once considered precious to the owners of the cameras. Since then, the owners may or may not have forgotten about the cameras, and because the owners did not change the factory settings, anyone on the internet can observe what these cameras capture.

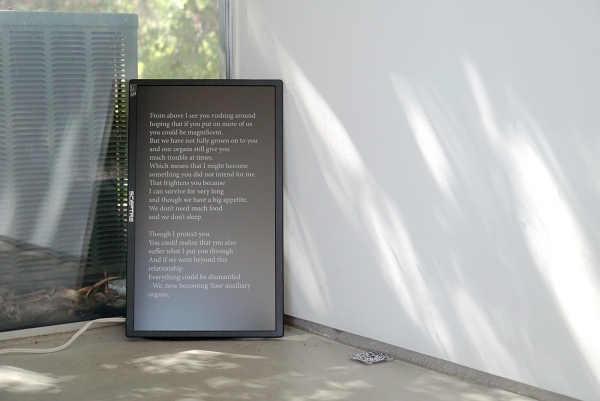

Dark Green Of Neither Earth Nor Sky is composed of photographic short stories derived from this archive. These spontaneous and mundane moments, rendered in stillness, speak to our increased physical isolation and solitude and dense digital connectivity and surveillance. The photographic sequences are coupled with a text exhibited on a monitor situated in the corner of the installation on the floor.

________

Against the dark doorway I see you

materialize out of darkness

You think you hear voices before you

reach the other door in front of you

Tilting a little down the hill, as the house does,

a breeze draws through the hall all the time, upslanting.

A feather dropped near the front door

will rise and brush along the ceiling,

slanting backward, until it reaches the down-turning

current at the back door:

so with my voices.

As you enter the hall, we may

sound as though we are speaking out of the air about your head.

For now, though, You begin to empty yourself for sleep.

Forgetting about me, you lay down looking up,

The tall buzzards hang in soaring circles,

the clouds giving them the illusion of retrograde.

In a few hours the moonlight will be on you and it will be still.

On me the moonlight will move, dappling up and down.

And before you are emptied for sleep, what are you?

You don’t know what I am, you don’t know if I am or not.

The rain begins to fall,

then eventually pour, on a road inside of

the perimeters You mapped for me

and outside of the perimeters You mapped for Yourself.

A runnel of yellow neither water nor earth swirls,

curving with the yellow road neither of earth nor water,

down the hill dissolving into a streaming mass of dark

green neither of earth nor sky.

Texts derived from

Exmilitary

William Faulkner

Mark Fisher

Sigmund Freud